She is able to do many things that are beyond the imagination of an ordinary woman: she climbs mountains, understands the peculiarities of a steppe ecosystem, easily reads the taiga like a book, hunts armed poachers, and plays billiards. She is able to do many things that are beyond the imagination of an ordinary woman: she climbs mountains, understands the peculiarities of a steppe ecosystem, easily reads the taiga like a book, hunts armed poachers, and plays billiards.

27 people work under her leadership. Twenty-three of them are men who are sparse of word and quick to act, who do not sit in offices, but perform their work of guarding the protected territories in their care. Animals are not afraid to meet them, but hardened poachers and criminals are; to win their sincere respect is a very rare thing.

Outwardly fragile but hard inside, she believes that everybody needs the protection of the Direction of specially protected natural territories of Republic Tyva that she leads: forest and water, hare and bear, little fish and small birds, but most of all - people themselves.

Her family speaks in four languages, but the are rarely all in one place.

Her husband is the American scientist Brian Donahoe, who is also an ecologist.

And today she lives in three countries - Chaizu Kyrgys, the dedicated protector of the nature of this planet, and, of course, of her native Tuva.

Childhood memories

Chaizu's parents - Suvan-ool Sendizhapovich and Alexandra Khovalygovna. Village Eilig-Khem, early 70's.- Chaizu Suvan-oolovna, how did you decide to become an ecologist? Chaizu's parents - Suvan-ool Sendizhapovich and Alexandra Khovalygovna. Village Eilig-Khem, early 70's.- Chaizu Suvan-oolovna, how did you decide to become an ecologist?

- Ever since I was a child I felt that I am a part of nature, because I was born on the banks of the mighty river Ulug-Khem. My parents lived in a beautiful village Eilig-Khem.

Now, unfortunately, it is gone; together with the surrounding rich valley forests, meadows and hay-growing areas, it was swallowed up by the Sayan reservoir. And this is a tragedy for people who have lost their native places, who have living memories of their childhood, and of places they will never see again.

My mother, Alexandra Khovalygovna, worked at the school as a teacher of Russian language and literature. She never objected when my father, Suvan-ool Sendizhapovich, used to take me with him on his rounds. He used to carry water for the sheep herders to their mountain stations in his water truck. He knew and loved the taiga, and he taught me to see the life of nature and to observe it.

- Just like in every Tuvan family, there must have been hunters in your family, too.

- My father used to tell us that he got his first animal when he was six years old.

He loved hunting, he was a member of a hunting association, hunted squirrels, and sables. Whenever he returned from the taiga, it was always interesting for me to see what he brought, and I loved to ask him about the animals and how he got them.

In winter, he used to take me fox hunting. Father also fished, with a rifle. He would climb a tree, looked for huge pikes in the transparent water, and shot them.

All this was terribly interesting to me. And it was not in vain, because everything that you learn in childhood is remembered for the rest of your life. The lessons in observing that my father taught me are very useful in my work today. The ability to read tracks, and not just animal tracks, is absolutely indispensable in our work.

It is possible to find out many things about an animal from its tracks: from the character of the tracks, it is obvious if the animal was running or walking calmly, it is possible to figure out its size, and to see how big it is in your imagination.

My younger sister Chainu and brothers Orlan and Syldys also received pedagogic education. But my brother Orlan shares my role of protector of nature.

They have no nature left

Chaizu with bicycle, in Ondum, 1990.- What do you think - did Tuvans have an ecological way of upbringing? Chaizu with bicycle, in Ondum, 1990.- What do you think - did Tuvans have an ecological way of upbringing?

- If we did not have serious ecological upbringing, our nature would not be as well preserved as it is. I can say that it is in good condition, I have some basis for comparison.

Why do the foreigners want to help us, organizing various foundations to protect our nature? When this question was asked at one meeting, they answered that they have no nature in its primal condition left, that many animals have been exterminated or their normal places of habitation have disappeared, so they offer their help so that it would not happen to us here.

For the Tuvans, ecological upbringing and consciousness has always been a big part in the upbringing, because the life of the nation was so closely tied to nature and depended on it.

- What was your path to ecology like?

- I liked all the subjects at school, but the thread of learning about nature, which started in my childhood, was never interrupted.

I went to various schools. In my native Eilig-Khem school, we used to go for excursions in the forest in our natural history classes,, I collected leaves and made drawings. At the school of the Arzhaan village, I went through compulsory practice - watering the vegetable garden. During summer vacations I used to help my grandmother to shear the sovkhoz sheep.

At Kyzyl school #3 I was sincerely enthusiastic about our biology teacher, Lidia Barfolomeyevna Osipova. How devoted she was to her subject! All the amazing flowers and plants around the school were the work of her own hands. And she gave her lessons as if she was acting in a theatre.

After school I advanced to the pedagogical institute in Kyzyl, and received the specialty of a teacher of geography and biology; I worked at the school in Teeli, and later at the Eilig-Khem school.

I got into the system of environmental protection when I started working as a scientific worker at the “Ubsunur depression” preserve in 1999. I had the good fortune to be a co-ordinator of projects in 2007 and 2008, and then a leader of the Altai-Sayan eco-regional department of WWF.

Now I am the supervisor of the republic government institution “Direction of specially protected natural territories of Republic Tyva”.

One of the guys - Chaizu

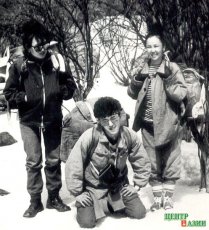

Ascent to Bai-Taiga. Left to right: Alla Konchuk, Eduard Sodunam, Chaizu Kyrgys.- I am sure that it is difficult for a woman to be an ecologist - to spend so much time in the taiga, to go on raids? Ascent to Bai-Taiga. Left to right: Alla Konchuk, Eduard Sodunam, Chaizu Kyrgys.- I am sure that it is difficult for a woman to be an ecologist - to spend so much time in the taiga, to go on raids?

- Yes, that is a special science in itself - to be in the taiga. It is not everybody who can live there for a week, ten days, or even more at a time. Some people become homesick, they miss normal food, and get tired of the cold and hunger.

But then there are those for whom it is like slipping into their native element. I would like to be like that too.

As a student, I loved to go on treks. Many of my friends from those times became famous people. One of them was Mergen Konchuk - he was famous as a multiple conqueror of Mongun-Taiga. He is not with us anymore.

We did not only climb mountains, we used to go on long winter treks of many days. Our leader was Saryg-ool Kara-Salovich Monge, who worked in the Center for children’s and youth tourism for many years. He was from Bai-Taiga, and he loved the mountains.

- And where did you go in winter?

- To the Sayan mountains; Krasnoyarsk people have organized their “Ergaki” nature park there.

It is not nearly as cold in winter as people think. The snowy taiga is warm in any weather. We used to put on a t-shirt, a warm sweater, a windbreaker, and pants with lining. We would walk on skis, which were just a little bit wider than the ordinary ones, and I called them “Forest skis”. We had a double-layer tent “Zima”.

At nine in the morning, we would have breakfast, during then day we would make tea and eat dry rations, and we would keep going until five at night. We would stop for the night, and everybody would do their job: two people sawed wood, two chopped, two cooked supper, and two would build the tent. We usually went in a group of seven or eight people. I was often the only girl among the guys.

Swallows on bicycles

Looks like something out of a Hollywood war film, but this is an ecologist on an expedition. Chaizu Kyrgys at Tsuger-Els of the Ubsunur depression.- What was the hardest part for a girl on those trips? Looks like something out of a Hollywood war film, but this is an ecologist on an expedition. Chaizu Kyrgys at Tsuger-Els of the Ubsunur depression.- What was the hardest part for a girl on those trips?

- The guys were so used to me that they did not even take me for a girl. We carried all our equipment with us, sometimes the backpack would weigh 15-20 kg. when it was difficult, I would jokingly get upset, oh, look, I am supposed to be the weaker sex, and my backpack is as heavy as those of the other guys. But I don’t remember any special difficulties.

We used to walk in the mountains in the spring, in winter we wou7ld go on skis, and in the summer we traveled on bicycles. We started a bicycle club “Kharaachygailar”, - “Swallows”. Our leaders were Oyun-ool Sat and Vladimir Amyr.

Once we took the bikes to Mongolia through Khandagaity; we went to upper Turgen and Kharkhyraa, that is beyond Ulangom.

I had a four-speed bicycle from the Kharkov factory “Turist”, for 230 rubles. How I managed to buy it on a stipend of 50 rubles, I don’t remember.

In the fall of 1990, we traveled in Todzha on bicycles fro two weeks. We took a boat “Zarya” to Toora-Khem. We visited Nogaan-Khol and Azas lakes. On the way back, we went through Iy, Yrban, Systyg-Khem, Sevi, Khut, and Turan.

On this trip I heard the roar of a maral for the first time. The Todzhans tried to frighten us, they said the taiga is dangerous because there were prisoner camps there.

- To meet prisoners in remote taiga sounds really frightening.

- Not at all. For them, to see new people in their remote bush was an event. They were so astonished as if we drove in with tanks. They were felling the trees and floating them down Pii-Khem. They had a farm there, some of them herded cows, others mowed hay. So the prisoners lived in the taiga during their prison term.

These student trips toughened me, I developed good habits, and learned the important art of being in taiga conditions. Everything became useful later.

- And why did you need to scramble through the taiga, ride bicycles over the dry Mongolian steppes, and climb up the snow-covered Sayans?

- And what is there to do in the city, except going to dances and to the movies? We were geographers, so there was also professional interest. We did not just want to see Tuva, we wanted to see other places, too.

There is a saying - “A smart person does not go to the mountains…”. I disagree with that. To conquer the mountains - that is a test, your own evaluation, and self-expression. Tourism is also interesting because of the impressions and new meetings.

- A young tourist became a geography teacher, who then went into science to become a candidate of biological sciences.

- I was greatly influenced by my instructors at the institute, Svetlana Surunovna Kurbatskaya and Lidia Kyrgysovna Arakchaa, who proposed that I work with them, and then to advance to an aspiranture at the Ubsunur international; center of biospheric research of the Siberian department of Russian Academy of Sciences. I agreed easily, even though I liked to work at the school.

I was very lucky that my scientific supervisor for aspiranture was Argenta Antoninovna Titlyanova, professor-doctor of biological sciences of the Institute of soil science and agro chemistry of the Siberian department of RAN. With my colleague Anna Sambuu, we became her Tuvan students, and I am unbelievably proud of it.

The steppe feeds all

- But did not science seem to your active nature to be something dry and boring ?

- No. I was not sitting in an office, I was studying the productivity of the steppe ecosystem in the Ubsunur depression. With its diversity of plants, you can compare the steppe to a huge table set with many different dishes. What does a person usually select among many dishes? Of course, the tastiest one.

And the animals also pick the tastiest among all the diversity of plants. Just taking one look at the steppe, it is obvious whether it is a sparse, average or rich table. The e well-known Tuvan “hot” grass - agy and kangy - wormwood and thyme, are considered to be very nutritious.

- To us, the steppe seems very monotonous and arid, yet in reality it is so diversified.

- For my scientific supervisor Argenta Antoninovna, the steppe is the love of her life. The steppe is really like the forest upside down. As the forest grows upward and its major biomass is above, so in the steppe it is the other way around. The underground biomass of the steppe plants is many times greater than above ground; in our steppes the ratio is seven to one.

The soil acts as a refrigerator or pantry; even after a fire or a drought there are stores of seeds. After a good rain, it is possible to see many plants growing in the steppe that were never seen there before. Nobody brought them and nobody planted them. That means their seeds were stored under the ground.

The steppe feeds everybody. Every animal has its own specialization. Sheep eat the soft grass. Goats adore the bushes on elevated areas. The hard plants that are left get eaten by cows and horses, which can deal with them. And when nothing is left except some thorny plants, the camels come to feed. It is very interesting to watch this.

Nomadic knowledge

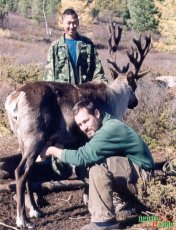

Brian Donahoe - came to Tuva to study Todzhans, as a result to fall in love and get married. In Todzha with the reindeer herders.- What can threaten the steppe ecosystem? Brian Donahoe - came to Tuva to study Todzhans, as a result to fall in love and get married. In Todzha with the reindeer herders.- What can threaten the steppe ecosystem?

- If a forest is chopped down, it takes a minimum of 50 years for it to grow back. But the steppe - it is a very stable system, but it can also be destroyed by overgrazing or by thoughtless ploughing.

Our steppe has not become impoverished thanks to the knowledge that Tuvan herders accumulated over centuries. They knew very well when and where to graze their cattle. In the spring, when the grass turned green, they went to the spring station - chazag. During the same period, a feast was growing at the winter station - kyshtag. And when they returned in winter, their “refrigerator” under the snow was full of untouched stores of food for the cattle.

In the summer, the herdsman would take his herd to the chailag - the summer station in high mountains, where there are water springs and a lot of grass, so that the animals would feed well and drink, and get fat. In the fall, when the grass wilts, and dries, the cattle goes down to the kuzeg - the autumn camp, where the late-blooming flowers are just flourishing.

The herders used to move each of the four seasons of the year. Now, since I am an ecologist, my heart hurts because of the fact that they stopped moving and the balance of nature was disrupted. The cattle does not go very far and they eat all the grass around the aal down to the roots.

- And what can be done to help the steppe?

- The steppe ecosystem must be protected by changing the pastures in the traditional schedule. And the system of wells has to be re-established; this is the opinion of my mentors Svetlana Surunovna Kurbatskaya and Lidia Kyrgysovna Arakchaa. Why do people now keep their cattle so close to the villages and water reservoirs? Because water is the most important resource.

During the Soviet times there were normally working wells in the steppes. Now they have all been damaged, but they can be re-built, because the actual drilled holes remain. There is also the system of aryks (irrigation canals). The nomadic system of our ancestors did not originate at random. They understood nature much better, they took good care of the steppe, and it fed them generously.

The Wild East

Chaizu with her son Dalai at the Niagara Falls; Brian photographed them.- Tourists from abroad come here and get enthusiastic: “How beautiful it is here! The water is so clean!” is it different elsewhere? Chaizu with her son Dalai at the Niagara Falls; Brian photographed them.- Tourists from abroad come here and get enthusiastic: “How beautiful it is here! The water is so clean!” is it different elsewhere?

- It is not necessary to think that they do not have anything at all, that everything is filthy and polluted, full of smog. Abroad it is clean, nice, but you can see the work of human hands everywhere. Even in the most remote places you can find a staircase, railings, or a bridge.

Here we don’t have stairs, nothing is prepared, and a person has to produce his own comfort. But that is where the adrenalin is. This is where the foreigners find their “Wild East”.

- Visitors to the republic, when they go to Lake Khadyn, can see right away our careless behavior towards nature. How do people elsewhere behave towards their own nature?

- I went to a seminar in Turkey and in the town Anatolia I saw that the people were very careful to keep their town clean. It was in winter, when there were no more tourists, but the caretaker was sweeping at the waterside and picked up all the small pieces of garbage. I don’t know, of course, what the place looks like in the summer, but in the winter the litter was literally blown away from the waterside and the water was absolutely clean.

In China I was surprised to see that this ancient civilization of many thousands of years survives in harmony with contemporary ways and with urbanization. They have their own culture, their own world. I was surprised by the amount of internal tourism. That is also an indicator of the Chinese people’s relationship to their country, to nature and history.

And nobody is trying to destroy it.

Brian has no objections to carrying Chaizu on his neck. Their wedding day on Mt. Khaiyrakan. 7 August 2004.- What relationship do the Germans have to ecology? Brian has no objections to carrying Chaizu on his neck. Their wedding day on Mt. Khaiyrakan. 7 August 2004.- What relationship do the Germans have to ecology?

- In Germany, there is practically not a single wild corner. We lived in Halle, two hours from Berlin. And you can always see roe-deer from the train. They move in whole herds and nobody bothers them.

- And aren’t the German roe-deer afraid of the trains?

- No. they graze in the fields around roads.

The Germans are a very law-abiding people, just like the Americans. There is no poaching. The radio, TV and Internet specially announce the beginning of the hunting season, and by that time every hunter already is registered and has a license.

But there is a limit, a quota - let’s say - 400 roe-deer. When the total number reaches 399, it is announced everywhere that there is only one animal left to shoot. Then the hunting stops. If you shoot the 401st roe-deer, you will be punished.

At all other times the animals can walk around calmly and feed. You can see foxes, hares, hawks hunting. In the park, nutrias swim freely, there are squirrels, ducks, geese, swans, and nobody tries to kill them.

And the USA is a huge country, and in contrast to Germany, it still has wild places. One has to be careful driving, deer can run out, drivers often collide with them.

There are road signs with a picture of a deer, just like we have road signs with a cow. The cows there do not walk about independently like in Tuva. Animals are kept in stables, and they are fed with special mixtures. There are many vegetarians there, because people do not want to eat genetically modified products.

And the cows with ecologically clean meat are kept in paddocks and can graze on green grass. Correspondingly, their meat is very expensive.

- And is the meat of an American cow different from the meat of a Tuvan cow?

- It is good, tasty, but ours is better. We used to buy frozen lamb from Australia or New Zealand. And again, it was not the same as Tuvan.

Garbage in his pockets

- Does your family share your attitude to nature?

- My husband Brian Donahoe is an ecological anthropologist, he studies the relationships between people and nature.

The territory of his research is, mainly, South Siberia and Todzha. His scientific work dealing with Tuva deals with types of perception of land ownership in the Sayans by Todzhans and Tofalars. He learned Tuvan to be able to carry out his research.

Brian is an American, but currently he works on contract at the Max Planck Institute of Social Anthropology in Halle, in Germany.

He is very careful about the resources, and I learn from him. He insisted that we install counters of hot and cold water in the apartment, and it turned out he was right - it was much more economical.

Of course, in our country we have a lot of water and electricity, but that is temporary, the needs of the population are increasing. It is good that lately people are forced to be more economical because they have to pay fort it.

My son Dalai is a first year student at Nizhnegorodskiy linguistic university, he is studying in the translator department. Brian and I met when my son was only five years old. They are very good friends, Dalaika calls him Papa, they do various men’s things together, where I don’t get involved.

Until recently, whenever I was doing my son’s laundry, I would find litter and garbage in his pockets. It turned out that if he does not have a chance to throw the stuff into a waste-basket, Dalai keeps it in his pockets. He is also has a lot of feeling for nature, just like his parents.

Not to hang on somebody’s neck

Brian Donahoe and Chaizu Kyrgys on their wedding day - at an ovaa.- Who is the head of your family? Brian Donahoe and Chaizu Kyrgys on their wedding day - at an ovaa.- Who is the head of your family?

- This question , I think, does not apply to us. A normal family could not function the way we do - I and my husband live in two different countries - Germany and Russia. And my mother-in-law Rosamond, who is 85, is inviting us to the USA, to Florida.

But I have already tried living in a foreign country, and I understand that it is not for me. It is very difficult for me not to do anything and just to hang on somebody’s neck - even a beloved neck.

- There is absolutely nothing to do for a candidate of biological sciences abroad?

- I could look for work at a school, university, but in Eastern Germany they have many of their own unemployed, and to be competitive, first of all you have to know the language perfectly, read, write. My German is at a beginner’s dialogue level.

I could go to wash dishes and get 800 EU for it. But it is not interesting, not because you are a candidate of sciences, but because you are working and getting money only for yourself.

In Tuva I get twice less than that, but I love my work. I understand young people who get a good specialization and stay in Moscow to work, or in other cities, or abroad.

My situation is totally different. I grew up here, I got my education and profession here, and I want to be useful to my native country.

- It seems that your life is like the proverbs: “Distance makes the heart grow fonder” and “Proximity breeds contempt”. Can you preserve your love at such a distance?

- We learned how to do it. When Brian came to Tuva in the late 90’s to study the life of reindeer herders, we became friendly, which then grew into a romantic relationship. It took us a long time and a lot of thought to get to the spouse level.

That is how we lived - he would come and go, and I would go to visit him. In Tuva we also lived separately - he would be somewhere in the taiga with his reindeer herders, while I would be at the nature preserve or on a working trip.

We got married in August 2004. Our wedding was in the taiga, in Tos-Teyek, at the summer station of my relatives Anna Khovalygovna and Mart-ool Kyrgysovich Damdyn, who are famous sheep herders -“Thousanders”. even now, whenever we have some time, we go to visit them.

American who speaks Tuvan

- What language do you use to communicate in your family?

- When we are living here, we speak Tuvan. When we are in Germany or America, we use English. My son speaks very good German, because he went to German school in Halle.

But now the three of us live in different cities, Brian in Halle, Dalai in Nizhny Novgorod, and I live in Kyzyl. My greatest dream is for Brian to come to live in Tuva after he finishes his contract, and for the whole family to be together.

- Is it difficult for people from different cultures to live under one roof?

- Difference of cultures always is a huge abyss, but we have overcome it.

At first in America things were difficult, because there was much that was incomprehensible to me; there was also the language barrier - I could not talk freely with my new relatives.

Brian is an ethnographer, he is studying the traditions and customs of our people, so for him it was easier to get over the differences in mentality.

To Brian’s credit, he has always tried to live by our customs. But what he does not like is to be the center of attention. I understand him now, even though before I used to be upset by it. He does not go to celebrations, because all the guests, even at weddings, turn their attention to him: “Oh, an American who speaks Tuvan.” everybody wants to talk to him, to get to know him. It is understandable - it is interesting to everybody.

But it can’t be said that he is not a sociable person. He has friends and colleagues from various countries, and he loves to be in touch with them. In Germany we definitely go to visit friends.

He is from a big friendly family with many children, the sixth among eight brothers and sisters.

What I liked about America is that I did not feel like an outcast that came from another world - black-skinned, narrow-eyed. Any person is protected and the law is always on his side, just like the attitude of the society. And here, as soon as you cross the republic’s border, they practically point their fingers at you. It is sad.

And even in the republic there was not the most tolerant behavior towards people who are not like everybody else. When we started being friends with Brian in 1997, I was afraid to walk next to him in Kyzyl. I felt that somebody might throw something at me, spit, or something like that. That is what it was like then.

And if they had found out that he was an American, they would have said that I was a girl of loose morals. So that is how we used to walk - either he was in front, or I was.

But I felt very quickly on my own case how things changed in our society. Already two years later we could walk in Kyzyl calmly side by side.

(To be continued).

|