She is one of those who know what to do with their life and what to do in this life to fill it with meaning and content. She is one of those who know what to do with their life and what to do in this life to fill it with meaning and content.

Literaturologist and folklorist Zoya Samdan is not a desk scholar. She has spent thirty-seven years collecting oral Tuvan folk art - tales and myths.

And Tuvan story-tellers, speaking in their native language and in Russian, have added their voices to members of other nations in the multi-volume series "Monuments of Folklore of Peoples of Siberia and Far East" - a huge project of Russian scholars from various republics that was begun in 1983 and continues to this day.

The epic connected with her work on two volumes of this series - "Tuvan folk tales" and "Myths, legends and traditions of Tuvans" - she considers a gift of fate.

And she is confident that this immense labor was not in vain; the folklore collected in the books of the series will be relevant forever.

Because it comes from the people and returns to them.

Time for Tales

– Zoya Bairovna, which fairy-tale did they use to tell you at night when you were a child?

– I don't remember them telling me fairy-tales, I liked to read myself, and especially Tuvan tales. So that nobody would prevent me, I used to get under a table with a long tablecloth, light a candle and read in my hideout.

Apparently it was predetermined by fate: stories that I used to read as a child became the subjects of complicated academic research in adult life.

– What is complicated about research of Tuvan tales?

– In their many themes and ancient sources - Turkic and Indo-Tibetan. The storytelling literature of the East had notable influence on Tuvan folk oral expression.

This phenomenon was studied by scholars Anton Kavayevich Kalzan and Gunga Ochirovich Tudenov, and the candidate dissertation of Antonina Saar-oolovna Dongak is on this theme.

The stories were brought from India to Tibet, from Tibet to Mongolia, and from Mongolia to us. Most of them were in a book format in the original, but we received them in the oral version.

There are various themes from the well-known cycle of Indian stories - so-called Birbaliana, and themes from "Panchatantra" a monument of Sanskrit narrative literature of the 3rd - 4th centuries. There also were texts named after the main heroes of Mongolian sources: "Ardzhy-Burdzhu", "Migir-Mizhit" and "Kol-Daryma".

– How did the people, without knowing how to read, learn about these ancient themes? – How did the people, without knowing how to read, learn about these ancient themes?

– Earlier, in Buddhist temples - khuree, Tuvan aristocracy and learned lamas used to gather. And what they had read in Mongolian language, they retold in oral form to audiences. And they told it to others.

– A tradition that remains to our times that on winter nights during celebrations of Shagaa - the New Year - stories are told all night - does it date to those times?

– Yes. On winter nights, from the time that the Pleiades constellation rises, is the start of story-telling time. But when the Pleiades disappear, it is time to work again.

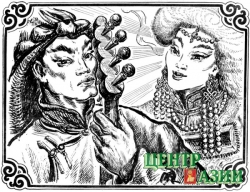

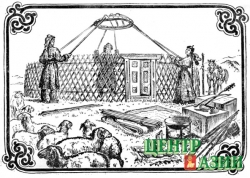

Ordinarily a story-teller - toolchi - could perform both tales and epics. An epic is a huge production, consisting of recitative prose or verse, but the story-tellers memorized them very well and would present them in the course of two or three nights.

The story-tellers had phenomenal memory! It is astonishing how much they could remember without being literate.

The tales had their hidden patterns, a typical poetic places: a prologue, description of the epic hero warrior, his horse, the golden princess - dangyna. And without departing from the basic pattern, each story-teller would add something of his own and improvised.

Story-teller - a Profession

– Did Tuvans have such a special profession - a story-teller? – Did Tuvans have such a special profession - a story-teller?

– Yes, but only those who had a gift of beautiful rhetoric, good memory and an interest in this work learned this complicated profession. The places most famous in Tuva for this are Sut-Khol, Mongun-Taiga, place Khenderge in Ulug-Khem, and Ovyur and Ulug-Khem Torgalyg.

The art of story-telling was usually passed from grandfather to father, from the father to his son. Tuva had entire traditional schools: story-telling school of Tyulyush Baazanai in Ulug-Khem, school of Shozhan Surunmaa dynasty, as well as of Chanchy-Khoo Oorzhak in Mongun-Taiga and Mannai Oorzhak in Sut-Khol.

If somebody wanted to learn the art from a story-teller of another family, they would give a horse for the teaching. Fro example Baazanai's mother gave her horse to the story-teller Kongarzhyk so that he would teach her son the art of story-telling. Todzha story-teller Bayan Balbyr, to learn the "Geser" epic, gave his horse to somebody who knew the story.

Everybody in the area would know where a great story-teller lived. On winter nights they would come even from distant places, bringing wood to keep the fire going all night, and they gave "kholun aktaar" to the story-teller - an eighth of tea, milk or meat products. That was not a fee for the tale, but an expression of gratitude from the audiences.

Story-tellers were extremely talented people. They were not just able to tell tales, but they were masters of all trades: stone-carvers, healers-otchu, and some could change the weather - chatchy.

– How many tales would they have in their repertoire?

– The average repertoire of a Tuvan story-teller was 20 - 30 tales. But some of them knew substantially more than that. For example, Baazanai had about 90 stories in his repertoire. Chanchy-Khoo knew 150, and Kongarzhyk 300 works. That is just what scholars were able to document in 20th century, they were not able to record part of the repertoire.

– You did not mention any women's names. Was it prohibited for women to tell stories?

– There was no prohibition on story-telling by Tuvan women, but there were very few female story-tellers, mainly they told short domestic stories about animals to children.

– A story-teller should never under any circumstances leave a story unfinished. Was there some sort of mystical meaning to this?

– Yes. Tuvans had an especially respectful attitude to the stories. A story was seen as something sacred, that is not allowed to be forgotten, hidden or performed carelessly. People believed that somebody who had the story-telling gift lived a long life, because with his talent he pleased the ear of the Master-spirit of the place, and was not attacked by impure or evil entities.

The story-tellers had a definite obligation to tell the tale all the way to the end even if the listeners fell asleep. They believed that there was Master-spirit of the story itself - tool-eezi - and the spirit-owner of the tale could get offended and punish the story-teller. There is even a tale about that - "Why it is impossible to hide a tale".

Magic power was ascribed to the stories; they believed that it helps to bring good luck in hunting. Hunters used to bring a story-teller along on hunting trips, so that he would tell stories by the camp fire. He would bring good luck and propitiate the Spirit-master of the taiga.

The story-teller, sitting on a shirtek - a felt rug - with his legs crossed in the eastern manner, closing his eyes and rocking, would enter the world of the story, taking the listeners along. And he had an equal share in the yield of the hunt.

The Last Generation

– And now, in the 21st century, are there any real story-tellers left? – And now, in the 21st century, are there any real story-tellers left?

– It is sad, but there are almost no real storytellers anymore. In 2008, before the 9th convention of story-tellers, there was a survey-expedition throughout all the districts of Tuva to search for candidates for participation. Some knowledgeable people were found, but the majority of them performed small genres - folk songs, kozhamyk - short songs, riddles. If they told tales at all, they were very short tales about animals.

Why were the archaic forms of story and epic forgotten? The first reason is that the need disappeared, people stopped listening because there was radio and TV. They are preserved in a more or less oral form wherever people live far from civilization, for example in the Tsengel sumon of Mongolia.

The second reason is the years of repressions, when shamans, lamas and storytellers were subjected to persecution. For that reason, even the fathers who knew the tales were afraid to transmit them to their children.

If the epic or the story is not told constantly, then the living existence of the performance is lost. If a father - story-teller died and did not teach his art to his son, the continuity is interrupted.

Today, only the last generation is left: children of storytellers who heard the tales from their fathers. They are already at the end of their years. It is one thing to tell the tales with all the typical poetic formulas, and another to simply re-tell the content.

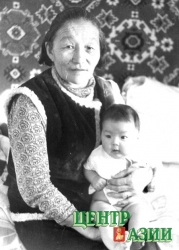

But I found a true treasure house of folklore. It is Bildirmaa Bazyrovna Samdan. Her maiden name is Banchyk, and she likes to be called Bortuk-Ugbai.

That is also a sign from fate. When I was hospitalized, Bortuk-Ugbai herself contacted me. We asked to be put in the same room, and in two weeks I wrote down 70 pages of unique material from her; I even forgot I was sick.

For a scholar, Bildirmaa Samdan is a real find: hereditary sheep herder, never went to school, never read a single book., but she knows Mongolian and Tuvan languages to perfection, knows folk pedagogics fantastically well, as well as medicine and folk cuisine.

She can do everything that a Tuvan woman is supposed to know, and even men's work: she sews clothes, kadyr idik - Tuvan boots with thick soles and upturned points, she makes things from tendons, she hunts, fishes, and rides horses. A true child of nature. She remembers things that happened when she was five years old as if they happened yesterday, and tells tales in a picturesque, bright and vivid way. There is not a single word of Russian in her speech. To her, a cell phone is - khol udazyny, honey is - ary myia, buckwheat is - kyrlan, beggar is - bok chushkuur, asphalt - alabatynyn aldyn saryg oruu.

Bortuk-Ugbai spent her whole life herding sheep in Kachyk, in a remote part of Erzin district. Now she is retired and lives in Naryn. Her father was a great hunter and used to bring his daughter along. Hunters who lived near each other used to hunt together, and they told stories to one another at night, that is why she knows so much.

She knows all the place names and histories associated with them. In the stories she tells of magachyn - a cannibal, about a camel, the sun and the moon, I recognized unique variants of myths.

Migrating Ivanushka

– Stories of various nations have the same themes. How can it be explained? – Stories of various nations have the same themes. How can it be explained?

– Scholars have come to the conclusion that during the earlier stages of human evolution, all the nations had the same psychology, and that is why tales have almost the same contents.

Contacts also have a large significance. For example, our story-tellers used to tell Russian tales in Tuvan manner, with Tuvinized names of the heroes and locations, with the theme remaining the same: Tan Ivanushka", "Six-year-old Iyvaandai", "Ivan-Baraban", "Khan Stepan". Those tales were known in Ulug-Khem, Kaa-Khem and Tandy districts, where both Tuvan and Russian population lived since 19th century.

There are many migrating themes, and even the term "wandering themes" - means international themes.

Study of tales is a serious science. There is even an international catalog of tale themes. It is just like Mendeleev's table of elements in chemistry - each theme has its numerical code.

When you mention, let's say, number 310 to any folktale scholar, whether he is an American, European or Oriental, he will immediately understand what the tale is about. And numbers 310a or 319b are already nuances of the theme.

This international catalog contains more than two thousand types of theme, and it is constantly adding more folk themes.

While studying Tuvan tales, I discovered eight themes that are not found anywhere else. For example heroic epos "Khaiyndyrynmai Bagai-ool" - "Bagai-ool with boiling energy". There is nothing reminiscent of European or Oriental tales there, it is completely ours - pure Tuvan.

So we are really enriching world folklore.

Not from the Oven but from the Buckwheat

– How long have you been studying Tuvan folklore?

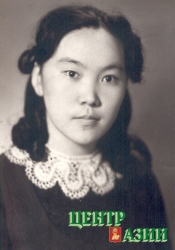

– Close to forty years. True, when I was in school the thought about some sort of academic philological activity never crossed my mind. I wanted to be a physician. But when I came to Kyzyl to enter college, there was no medical institute program, and I applied for the psychology department at Moscow State University. I passed the exams wit all A's and one B, my relatives were very happy.

But at MGU they took a graduate who already had work experience. They suggested that those who did well on the exams could select other spots. They talked me into going to the chemistry department at Irkutsk State University.

In the first year, they began right away with higher mathematics, and I understood that it was not for me. I started to get ready to go home, and then the unbelievable happened: the Dean of the university personally invited me, a freshman, to talk to him. "Why don't you want to study? We have a contract to take five people from Tuva on state expense, and we are obligated to produce five specialists." In the first year, they began right away with higher mathematics, and I understood that it was not for me. I started to get ready to go home, and then the unbelievable happened: the Dean of the university personally invited me, a freshman, to talk to him. "Why don't you want to study? We have a contract to take five people from Tuva on state expense, and we are obligated to produce five specialists."

I got shy, babbling something about my tendencies towards the humanities. And then the dean proposed , as an exception, that I could pick one of four departments - journalistic, law, history or philology. He gave me two days to think about it.

I did not understand my luck, and I went on to hope to go home and to be transferred to Kyzyl pedagogic institute, but my uncle Vasiliy Amyrdaayevich Kopeel convinced me telephonically to continue studying at the philological department at Irkutsk Sate University : philology is a multifaceted specialty, one can be a journalist, a teacher, or a scholar.

So I listened to his advice and chose the philology department. It was not easy at first either,, everybody around me seemed to be so smart! But gradually I became absorbed in the study, so that I did not even miss home anymore.

I became especially absorbed in an assignment given to me by philology lecturer Anastasia Grigorievna Mitroshkina after the second year: During the summer vacation, collect all the information about the toponymics of your native district."

The work on the toponymics - the origin of geographical names in Tes-Khem district - I found really absorbing. I questioned thoroughly and in detail all the old settlers during the summer of 1970, and collected a tremendous lot of material about the origins of the names of village Samagaltai, mountains Saigyn, Tugluga, Kazanak, the Kaldak-Khamar mountain pass, and rivers Tes, Uzharlyg-Khem, and Dyttyg-Khem.

I put my whole soul into the assignment, and I wrote a small but independent academic work. Soon my term paper :"Microtoponymics of Tes-Khem district" was on Anastasia Grigorievna's desk.

– It is interesting: even though most people start with an oven you started with a river. Is Samagaltai, where you made your first humble step into academics - your native place?

– Yes, I was born in Samagaltai on 22 April 1951. Our house was near the place where once was Samagaltai khuree. The temple has long been demolished, but we often found colored fragments from the monastery that used to be previously so rich - we used them to decorate our saizanak - toy stone constructions.

To me, the main and the most loved building of the village was the school. At one end of our street was a hill that seemed to me to be a large mountain when I was a child, and from that you could see a whole world - the school campus. I wanted so much to go there! With tears in my eyes, I begged my brothers to take me along when they went to their lessons. To me, the main and the most loved building of the village was the school. At one end of our street was a hill that seemed to me to be a large mountain when I was a child, and from that you could see a whole world - the school campus. I wanted so much to go there! With tears in my eyes, I begged my brothers to take me along when they went to their lessons.

To calm me down my mother got a school uniform for me early, put it over my shoulders, and tried to convince me - here, you already have the uniform, now you only have to wait a little, grow a little bit more…

Just before the first school day, I had a dream: Mynchaak-Bashky - teacher of the first grades Mariya Sanaayevna Enaa, smiling, handed me the "Uzhuglel" - the first writing-reading textbook. My mother thought it was a good prediction for study. And that is exactly what happened: I really loved school.

At that time, the Samagaltai school had a very friendly, strong international working team. Anna Mikhailovna Malanicheva opened the world of Russian language and literature to us in the middle grades. In the higher grades, our teacher Mikhail Nikolayevich Borsoyev supported and developed our love of these subjects, and determined my future.

One of my beloved teachers is also my class head in the senior grades, teacher of social science - Sendenmaa Alexeyevna Sat, who is in good health and now lives in Kyzyl. Friendly families of teachers Demchikov, Chyndygyrov, Kochara and Taraachy also worked at the school.

They prepared us for practical life as well. In workshop classes, we learned to work with wood and iron.

In housekeeping classes we cooked, sewed, we even learned to diaper babies, training with dolls. During Saturdays we dried hay, prepared wood, planted potatoes, we made bird-houses. In the summer, we collected berries, nuts, and hunted gophers.

Our whole class loved skiing, basket-ball and volley-ball. And also - choir and dance clubs, and annual exhibition of individual art, trips to sheep herders as propaganda teams.

So that school for me really was my second home, but the third was the old Samagaltai club. Back then there was no television in the village, and every evening everybody went to the club to see a new film. Cinema played a big role in bringing up our generation.

Efforts of our teachers were not in vain. So many people are among my classmates, graduates of 1968: Larisa Bair-ool, Alexandra Borbai-ool, Sergei Enaa are physicians,; Tamara Kungaa, Viktor Kara-ool, Taya Oyun, Larisa Poleva are teachers; Volodya Kolevatov, Volodya Kuyukov and Leva Sando are engineers; Anatoly Samdan and Sergei Sanchan work in law enforcement; Raisa Dogui-oool works in finance; Nadezhda Temir-ool is a librarian.

Guilt before my father

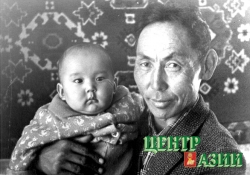

– Who were your parents? – Who were your parents?

– Mother, Oyuu Bulchunovna Arakchaa worked as a seamstress all her life at Samagaltai clothing workshop,; she was a very skillful seamstress. Everybody in the village knew her under her domestic Buddhist name Kamaa - goddess of love in translation from ancient Sanskrit language.

I was 12 when my mother got very sick. Ten years later she left this life, but she managed to inculcate love of work and responsibility in all of us - her seven children.

Papa, Bair Amyrdaayevich Arakchaa worked as a bookkeeper and everybody called him that - Bugaldyr - after his profession. For a long time I did not know anything about our family tree in his line. As a child, I used to hear the word "contra" in my parents' quiet conversations, but I did not understand what the word was all about that came down to us from the times of repressions.

Today reminders of that time come up in my memory: there were people with names like Stalin, Stal, Malenkov, Kirov, Shchors, Chapai in the village. The chiefs were very respected, people called them respectfully "darga" and were afraid of them. They ridiculed lamas and shamans. Traditions and rituals of the people were considered as relics of the past.

Only much later I found out that my grandfather Choodu Chyrgal-ool was a lama of the Samagaltai khuree, and my father, as a young man was a novice student there. My father was expelled from the communist party for such "counter-revolutionary" descent, and he was even sentenced to two years.

Papa tried for many years to get reinstated in the party. To achieve that, in his old age, already as a pensioner, he worked for several years as a yard-keeper; he used to clean the yard of the House of Political Education in Kyzyl; it was a part of the district headquarters of the party. Now it is the House of national Art. In the end he achieved reinstatement, he was very happy, and the next year - in 1991 - the communist party collapsed.

Do you know, to this day I feel guilt before my father. After Mother left us, he lived in my family for more than 20 years. He lived right next to me, and I never bothered to write down the old histories; and he knew so many of them. Do you know, to this day I feel guilt before my father. After Mother left us, he lived in my family for more than 20 years. He lived right next to me, and I never bothered to write down the old histories; and he knew so many of them.

Whenever he asked me, who was already seriously involved with Tuvan folklore, to write down what he knew, I used to refuse and go off many kilometers away to the districts to seek other old informants.

That is how we were trained during the Soviet era - never to record those close to you.

Papa died when he was 88, in 2000, in the year my first grandson Sasha was born. After he left, I began to go through his old documents, papers, and I felt acutely my carelessness and guilt before him. He knew a tremendous lot about the old times, he knew the family trees of all the people of his generation who were from Tes-Khem and Erzin districts, but he took all that knowledge with him.

Among Papa's papers I found a manuscript of a toponymic myth "Ulug-Khaiyrakan, Biche-Khaiyrakan and river Tes" - about the origin of those names. I included it in the volume "Myths, legends and traditions of Tuvans", which was published in 2010 in the multi-volume academic series "Monuments of folklore of peoples of Siberia and the Far East".

At the end of this volume, there are many indexes; lists of names of the personages, toponyms, collectors of the texts, locations where the texts were recorded, and of course, index of names of performers. Among them are names of prominent performers of myths and legends Agyldyr Maskyrovich Mongush, Khurgul-ool Sazyg-Khunayevich Mongush, Orus Dongur-oolovich Kuular.

When I included the toponymic myth that my father wrote down in the volume, I fulfilled my debt to him and atoned for my guilt. Now his name as well is among the names of the old experts of Tuvan folklore.

to be continued...

|