Fate, like a stubborn untamed horse, tried many times to throw him to the ground, but the rider never let go of the reins and conquered the racehorse. Fate, like a stubborn untamed horse, tried many times to throw him to the ground, but the rider never let go of the reins and conquered the racehorse.

Today he is proud of his titles: Meritorious artist of Russian Federation, National khoomeizhi and Meritorious worker of education of Republic Tyva. He is known to world idols of rock-music, Tuvan, Russian presidents and American ranchers.

But, regardless of apparent openness, Kongar-ool Ondar is a man of mystery. Behind the artist's wide smile shows no hint of his difficult fate: hard childhood, burden of years spent behind barbed wire, and the secret of his birth, which torments him to this day.

In the year of his fiftieth birthday - at the boundary of making sense of the years he survived - the master of khoomei decided to tell "Center of Asia", openly, without embellishments, about the times when he despaired and hoped, fell and picked himself up again.

And how khoomei helped him to stay in the saddle - Tuvan throat-singing, to which Kongar-ool Ondar dedicated his entire life.

NOT A SPOILED CHILD - A STEPSON

- Kongar-ool Borisovich, looking at your constant smile glowing from the stage, one gets the impression that you are a carefree spoiled child of fate.

- It is not like that at all. I am no spoiled child of fate. More like a stepson. If I go through my whole life, it is a story of a hard fate.

I did not get anything in life the easy way: there were betrayals, hurt, humiliation, and I made mistakes for which I paid dearly.

I was silent for many years, and did not tell anyone about these things. But now the time came to make sense of the past and I am ready for an open talk.

- But why are you always smiling as if your life was very easy and cheerful?

- Out of spite to all the circumstances. The worse I feel, the more I smile. I do not want the bitterness to poison me from inside.

- Wasn't there anything bright even in your early childhood?

- Everything good and bright in my life is associated with my early childhood. My first memory is of a beautiful place where our yurt stood, my mother's parents - grandma Balchyt Ondar and grandpa Dokpak Mongush.

They raised me. We lived in Iyma village, but we moved around during all four seasons: winter at kyshtag, the winter camp at Seseg, in the spring - to chazag, summer to chailag, and in the fall, to kuzeg.

The taiga summer pastures near the Adar-Tosh pass and near Kegeen-Bulak were especially nice.

- Certainly, with your grandma and grandpa, you grew in love and care like a sheep's kidney in fat, as Tuvans express it, or in a Russian expression, sliding around like a piece of cheese in butter?

- Yes, it was like that. Everybody was afraid of my grandfather, they said that he spent nine years in prison, where he learned to speak Russian really well. But he loved me very much. I could fall asleep only in my grandfather's arms.

When I was little. I thought that my grandma and grandpa were my parents, and I called them avai and achai, mama and papa. When I grew a little, I found out that I had a mother Serenmaa. She was at school in the city at that time and sometimes she came to see us.

Then my mother had a wedding. She married a man from the Dongak clan and took his name, but I remained Ondar - it was my mother's and grandmother's last name. so that is how I found out that I was a suras - fatherless.

My mother is now over seventy, but I still gall her ugbai - older sister, or talk to her without addressing her directly. I consider grandma and grandpa to be my real parents, who had gone for the red salt a long time ago.

- And does this attitude not offend your mother?

- It is I who should be offended at her, not she at me. In the fifty years of my life, I still was not able to find out the name of my real father from her, and to this day I don't know the exact date of my birth.

Regarding my father, I have only some guesses. It was said that I am a son of a man named Saiyn-ool. He worked as an engineer in our village, was married, and his daughter is two years younger than me. I saw him often in childhood.

When I was seven years old, there was a motor vehicle accident on a working Saturday: Saiyn-ool and the foreman crashed on a motorcycle. The foreman had injuries, but Saiyn-ool died. I ran to the accident site together with everybody else, and I remember that people , when they saw me, whispered: "Look, his son came."

Much later, his grandson Ertine became one of my students, at the republic art school, and I taught him to sing khoomei.

I do not know if I look like Saiyn-ool or not. But countrymen are always saying: "You are his son." That is why I named my younger son Saiyn-ool, so that they would leave me alone.

My father is only one of the mysteries of my life. The second one is the date of birth.

WITHOUT EXACT BIRTH DATE

- But what problem is there with your birth date, isn't it normally on the birth certificate?

- But I did not have any birth certificate at all! More than that, I even had several names.

It is because grandpa always called me Valerka, and that is what the older generation in Iyme village still calls me. On the morning of September 1, 1969, when I went to the preparatory grade in our village school, grandpa said that my name was not Valera, but some Tuvan name ending in "-ool", and told me to remember it well.

All the way to school I repeated it to memorize it, but at school I completely forgot it - there were so many new things and everything was so exciting on the first day of school, especially the teacher - Lidia Borisovna Sanchat, the mother of Titov Sanchat, who later became a famous singer. She was so beautiful!

We were all lined up ceremonially, and she came up to each one of us and asked our names. Then it was my turn. And I became nervous and did not know how to answer such a simple question.

The teacher asks for my name, and I could recall only the first letter "K" and the ending "-ool", and everything in between just flew out of my head. What to do?

Suddenly my sight fell on an old man from our village, Kongar-ool. I blasted out his name, because it seemed similar to whatever my grandpa told me.

Then Lidia Borisovna asked for my surname, and I knew that one: Ondar. Then there was again silence for the patronymic, I did not know what to say. People told the teacher my grandpa's name: "He is Dokpak's son."

So that is how they registered me: Ondar Kongar-ool Dokpakovich.

But when she asked the date of birth, I got anxious again, because I did not know it. My classmate Kostya's mother helped out, she offered: "We were together at the obstetric hospital with his mom Serenmaa. He was born one day before my son. Since my son's birth date is December 5, 1962, his has to be December 4, 1962.

So, based on testimony of various witnesses, this is how my personal information was registered at school.

- But if you were born on 4 December 1962, why did you give the big concert in Kyzyl in honor of your 50th birthday on March 30, 2012?

- Because in my passport, I have the date of birth as March 29. Relatives, after trying to remember when I was born, recalled that there was snow, but it was warm. And they decided that it must have been in the spring, at the end of March. So this way this agreed-upon birth date showed up - March 29.

But December 4, somehow feels warmer to my heart. I don't think that my classmate's mother would have made a mistake, when she told the teacher the date when I arrived in the world.

So I celebrate my birthday twice a year - on March 29 and December 4.

- And what about the name that your grandpa gave you on September 1, did you ever remember it?

- I never even tried to remember. I called myself Kongar-ool, I lived with it, studied under this name, which was registered in the personal file and moved with me from the Iyme school to the school in Chadan. After my mother got married, she soon had another child, and they took me to Chadan - to be raised with my little brother.

After eighth grade, to get the graduation certificate, a birth certificate was required, which I had never seen in my life. None of my relatives could say exactly where it was or if it ever existed.

Then the teacher's husband went to the district archive to search. And it was discovered that Ondar Kongar-ool Dokpakovich never existed.

They only found an entry which listed my mother's name, the father's name rubric was crossed out, and the baby was listed as Ondar Kagar-ool Borisovich.

It turned out that grandpa, in honor of Gagarin's cosmic flight in 1961, named me Gagar-ool - Tuvan variant of the last name of the first cosmonaut. And when they registered the name, the unusual name changed into something more familiar to the Tuvan ear - Kagar-ool.

And when the teacher announced to the whole class that according to documents I was not Kongar-ool but Kagar-ool, all twenty boys of my class almost fell over on the floor with laughter, and I almost burned to death from shame. And on top of that the patronymic turned out to be not Dokpakovich but Borisovich, God knows from where.

- But why did they laugh over your name, after all, kagar in Tuvan means to strike, what is so funny about it?

- That is true in the literals sense, but in the vernacular, the word kagar has a shameful meaning connected with sex.. And that is why my classmates rolled on the floor with laughter, and I turned red from embarrassment.

This hated name Kagar-ool became my problem and obsession. I was active in sports at school: I was good in running on skis, volleyball, basketball, and I never missed a touristic meet. In 1979 I participated in Kabardino-Balkaria in competitions in sport orientation. Our Tuvan team came in the 20th place out of 72 teams of the country.

But at the competitions, when you are over 16, you have to show your passport. You can't imagine what lengths I went to to avoid that. I even stuffed my passport under the insoles of my shoes. All my friends were entertained by it.

In tenth grade I went to the district administration office and requested to have my name changed to Kongar-ool, I submitted an application, and got rid of that shameful name. But somehow it did not occur to me to change the patronymic.

The patronymic from my grandfather's name, Dokpakovich, would have been better that the incomprehensible Borisovich registered at the district office.

Legend of Borises and Borisoviches

- But why did they register you as Borisovich?

- It always amazed me. There was nobody in our village named Boris who could have been my father based on age. But one old lady who used to work as a midwife used to say that in the end of the '50's, early '60's, a Russian darga - a chief official - used to live in our district, named Boris. Supposedly he was a good person who solved the problem of children whose patronymics were problematic - he told the matrix clerk: "Just register them all under my name - Borisovich."

It is possible that it is only a legend, but there really were boys in the district who had no known fathers, and, just like me, they carried the patronymic Borisovich. And the name Boris was very popular at that time.

I began to reminisce and I realized that in the Iyma village, there were Borises in almost every household: Boris Mongush, Boris Sukterek, Boris Sygyrtyr, Boris Dygyndai, Boris Mytpyla, Boris Kochugur, Boris Kok-Karak, Boris Sedip-ool, Boris Dovukai, Boris Dyrtyi-ool. Every family with many children had one child whose name was Boris. I began to reminisce and I realized that in the Iyma village, there were Borises in almost every household: Boris Mongush, Boris Sukterek, Boris Sygyrtyr, Boris Dygyndai, Boris Mytpyla, Boris Kochugur, Boris Kok-Karak, Boris Sedip-ool, Boris Dovukai, Boris Dyrtyi-ool. Every family with many children had one child whose name was Boris.

So this seems to confirm the words of the old midwife, but it is only one of the versions.

- And how did all these Borises and Borisoviches live?

- Interestingly and cheerfully. At that time, we had many amateur artistic contests and competitions between streets and neighboring villages. The whole village was excited by it. There was not a single household where the people would not be involved in the activities.

How the village people loved those talent contests! They sewed the costumes, prepared, rehearsed with great inspiration. Where did it come from? They made intricate decorations, made benches for the choir, assigned responsibilities, thought everything out to the smallest detail, down to who is to bring what to the club. We kids took a lively part in it.

Each street definitely had its own khoomei master. After the concerts, everybody argued who was better at throat-singing, who had what style and idiosyncrasies, whose ensembles, men's or women's choir was better, they bragged about their artists. Back then the fame of the prominent khoomeizhi Maxim Dakpai was rampant.

The victors were rewarded with trips to Khovu-Aksy or to Shushenskoye; a bus was chartered, and whole families, whole street went on the trip. It was unforgettable.

BRUTALITY BREEDS BRUTALITY

- When they took you to Chadan, did you miss your native village Iyme very much?

- Of course I missed it, but just like any other child, I would have gotten used to the new place easily, if it weren't for one serious circumstance: my step-father, a very nasty and brutal man, hated me.

I was a burden to him. And I was aware of it very much myself: everybody in the family had the surname Dongak, only I was Ondar. My step-father made a sharp difference between his own children and strangers. If it seemed to him that I was harming my younger brothers, his real sons, he would smack me without any ado. I was so terrified of him that I would come home only after everybody else was asleep.

Boys at that time loved to go to the movies. To make money for the ticket, I literally licked everything clean at home, so carefully I cleaned. Sometimes my step-father gave me some money for the work, but sometimes not.

I was very careful not to anger my step-father. I was a good student at school, I took active part in all the amateur artistic festivals - I sang, danced, did sports. But my permanent headache was the cow, or more exactly her permanent absence.

We lived at a distance from the center, our house was in a forest not far from the destroyed temple Ustuu-Khuree, and in the spring the cow liked to go grazing on grass far, far away. I still remember how I used to search for her, way until dark.

It was impossible to return without the cow, my step-father would beat me up for that. It would often happen that I got back with nothing, was afraid to go home, and would go to sleep in the hayloft, then soon wake up from the cold. But the cow would show up by herself in the morning, well fed and pleased with herself, as if nothing had happened; out of rage I would smack her, then quietly creep into the house, and right away to the stove - to the warmth.

Once after such an adventure I was quietly warming myself up by the stove and I fell asleep, leaning with my elbow at its iron edge. I woke up from a sharp pain - I burned my elbow. I screamed, cried , and my stepfather jumped out of the bedroom, shouting: "You woke me up!" he gave me a beating and threw me out on the street. I still have the burn scar as a memento.

- And your mother did not defend you?

- Mom was afraid of him and could not do anything. When I already had finished school, he abandoned her and went to live with another woman. I never saw him again. - Mom was afraid of him and could not do anything. When I already had finished school, he abandoned her and went to live with another woman. I never saw him again.

Once after one of the first concerts of "Tyva" ensemble in the district, people told me: your step-father stood in the doorway of the auditorium, watched you and cried.

It is true that everything comes around - brutality breeds even greater brutality. His own son, when he grew up, used to beat up his aged father.

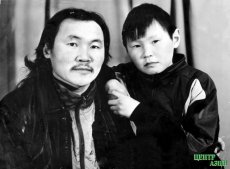

A child should have a father - loving and dependable; it is something I realized already during my school years, and I decided that I will always be right next to my future son. But, as it turned out, circumstances in one's youth are stronger that your most burning wish, and I was not able to raise my first son.

FIRST LOVE AND FIRST CONVICTION

- Why did it happen, did your first marriage not work out?

- There was no marriage as such. My first love lived in Chadan, and studied at the Kyzyl medicine school. We were eighteen years each when our son was born. Naturally, we dreamed of a life together, but it did not work out - her parents were against it: they were respectable people of substance, and I was naked as a newly hatched bird, a beginning self-taught artist.

To prove that I could support a family, I sang and played guitar in an ensemble at the House of Culture in Chadan, worked as a guard at the hospital, took courses as an auto mechanic at the school. But it was all in vain. They did not let us be together, and his grandma and grandpa registered Chingis under their last name, changed even his patronymic and did not let me see him. It was very painful for me.

Chingis is now thirty-one. He knows I am his father and is proud of me.

- Kongar-ool Borisovich, at one time there was a lot of rumors about your criminal past. Is it true that you were convicted twice?

- True, why hide it, and the first time it was a suspended sentence. That happened when I was just a beginning professional artist. In 1982, when we came with an amateur ensemble "Sygyrga" from Chadan to Kyzyl, a turn-around happened in my life: the deputy minister of culture Valentina Vladimirovna Oskal-ool noticed me and decided to send me to Leningrad - to study at the art atelier of estrada arts with Khisat Aminov's group "Cheleesh".

I studied for three months the basics of professional art as well as an announcer. My certificate states: master of verbal genre.

When I returned home, I was given a room in the wooden dorm of the Philharmony, and tours began in the republic.

When I had some time off, I went to Chadan. I met with friends by the cinema, with whom I used to play in the ensemble. One of them asked to change clothes with me, he wanted to show off in my fashionable Leningrad outfit. We switched.

So I am standing there, in somebody else's jacket, talking with friends, and suddenly he comes running back, enraged - he had a dispute with somebody, and he is shouting: : "I'll deal with them. There is a knife in the pocket of my jacket - give it to me!" well, I think - he is seeing red, and he'll do something crazy in a fit. I could feel the knife in the pocket, and quickly hid it in the sleeve, and I answer: "There is no knife here." The owner of the jacket ran off.

Right then, bass-guitarist Radik jumped out of the cinema when he saw me. We had not seen each other in a long time, and were happy. We shook hands, and Radik ran back in - his session began.

I am standing there in a long scarf, just like a stylish guy from Leningrad, proudly telling everybody about my life in the big city, when suddenly the ticket-woman from the cinema runs up bringing the militia, points to me and yells: "That's him, he just stabbed a guy!" I am standing there in a long scarf, just like a stylish guy from Leningrad, proudly telling everybody about my life in the big city, when suddenly the ticket-woman from the cinema runs up bringing the militia, points to me and yells: "That's him, he just stabbed a guy!"

They began beating me, twisted my arms back, and the knife that I hid from my friend and that I forgot about, fell out of the sleeve. It turned out that when I shook hands with Radik, I injured his hand without even noticing it. At the cinema, his finger was bleeding, and the woman called the militia.

I was confident that they would let me go, but that evening, my first love's father was on duty - he was a militia captain. And he did everything in the world to make something out of this silly accident - he wanted to thoroughly get rid of me. My school teacher Mikhail Vasilyevich Borbai-ool, and many thanks to him, went from place to place, requesting, pleading, trying to get me off the hook. Thanks to him, I got three years suspended sentence, for hooliganism in a public location.

It was very difficult at that time, and I decided to run away from it all to the army. But it did not work out either. I served only seven months. As soon as I finished training, I was assigned to sea border patrol in Kamchatka, and an unfortunate accident cut off my service.

When we were unloading containers with bags of flour and sugar, those who were handing the bags down from above, clumsily threw a seventy-kilo bag on my back. Everything went dark, and there was such a pain in my spine.

At the hospital, I was in a body cast for over a month. The diagnosis was subluxation of the sixth cervical vertebra. And I was discharged from the army. They gave the order, the documents, but I begged them: "Please assign me to the Far East border district ensemble, I am an artist and I could serve that way". But they gave me a plane ticket, and my army career was over.

I went back to Kyzyl, and my friends had a party for the "sea wolf". I sang and played the guitar all night. The concert went on till the morning. And the next morning I was invited by Marina Mongushevna Gavrilova, the dean of the philology department of Kyzyl pedagogic institute. We had a short but, as we would say today, constructive dialogue : "My students told me about your concert last night. They say that you have talent. I need people like that. Will you study?"

I was terribly surprised, and I asked: "You mean at the preparatory department?" ?No, in the first grade of the philology department." So, in December 1983 I became a student.

I barely started to believe that the bad luck streak in my life was over, and that it is the beginning of a bright, white streak, but it still did not work out - I became involved in a nasty situation, which ended up in a real sentence this time.

INSTEAD OF A PROCURATOR'S SON

- What was the nasty situation, Kongar-ool Borisovich, that cut off the white streak of your life?

- It was a brawl that took place on 1 January 1985, and turned me from a student of the philology department of the pedagogics institute into a convict. This is how it happened. Boris Dembirel, Valeriy Shivit-ool and myself lived in room 523 of the institute dorm on International Street. The men's rooms at the dorm were usually horribly messy, but ours was ideally neat. I even put a rug on the floor and made everybody take their shoes off and walk only in socks in the room.

Guys who came to visit were astonished: so clean, as if girls lived here. But the dean, Marina Mongushevna Gavrilova, praised us: Kongar-ool keeps the best room, like an ideal showroom example.

When one of my countrymen, and I won't mention his name, was admitted to the preparatory section of the philology department, I was very glad and offered him to move into our showroom example room.

On the new year of 1985, he proposed to meet with his girlfriend and her friend. In the evening, we went to the theatre of music and drama to the New Year's ball. The ball was cheerful, I participated in all the contests, and won three prizes at the same time - for sygyt - throat singing, for dance, and running in a bag.

Then we went to meet the holiday at the girls' place - in a communal apartment. There were other people living in the four-room communal apartment, who also had guests celebrating the new year. On the first of January, my friend ran into one of those other guests in the hall, and started a dispute. But I put my jacket on and ran away to the street to keep out of trouble: "I have a suspended sentence, I have to stay away from  this kind of thing." this kind of thing."

I was already outside, when I heard the noise of falling furniture and ringing of broken glass. So why did I, like an idiot, run back? I can't understand it to this day. Nevertheless, I ran back: how can one leave a friend, and the girls were desperately screaming in the apartment "Help!!"

Then it all turned into a nightmare. When I ran back to the apartment, those fighting tripped me onto the floor. Then I grabbed something, the first thing at hand, and threw it at them from the floor. It turned out to be a shard of glass. It struck the unknown man with whom my friend was fighting, on the head. His head started bleeding.

Then the militia came, grabbed us, and took us to the precinct.

My friend's father was a procurator of a remote district. He bailed us out of the precinct, but a criminal case was initiated, investigation was started, and we were interrogated.

Soon my friend's father came to have a talk with me. I could guess beforehand what he was going to say, and I was right. "Let's talk man to man, - he said. - You have a suspended sentence, so you will go to trial no matter what. So let's get my son out of it. It will be easier for me to get you out when there is only one."

I agreed, even though deep down I had doubts, but the procurator promised so seriously, that I believed him and took all the blame at the next interrogation.

INSTEAD OF AN INTERNATIONAL YOUTH FESTIVAL - A TRIAL AND A JAIL TERM

- So did the procurator keep his word, or did it turn out like in the song: "But the case was not adjourned, and they announced the sentence. And they gave me everything they could, plus five more from the procurator."

- It was almost exactly like in the song.

In the spring of 1985 everybody talked only about the twelfth International Youth and Student Festival, which was supposed to start on 27 July in Moscow. And I had a chance to get to this festival!

The selection of the young artists who were to perform in Moscow, went on in Novosibirsk in the regional festival, and they invited me to perform throat-singing there - to represent artistic youth of Tuva and folk arts. At the republican center of folk arts they picked a beautiful folk costume for me, and a musical instrument - doshpuluur. They even got the plane tickets for me and the others.

I was already dreaming about it: I'll come to Novosibirsk, I'll pass the selection, and will go on to sing in Moscow - at the International Festival. But it was completely different!!!

On the day of the departure, on 5 June, a militia man came to our students' dormitory, and says: you are asked to come to the city department - just for a little while. So I go, and like a simpleton I tell them, that I don't have much time, that I am leaving for an important contest today. So there immediately was evidence that I was preparing to escape from an investigation, and they took measures right away: they shaved me and threw me into a cell - an investigation isolator.

After twenty-two days, the announced the sentence - six years of loss of liberty in a corrective work colony with reinforced regime.

I was in shock - after all, the procurator promised to get me out! But instead they put all the blame on me.

At the trial, the man who was injured in the fight told the truth anyway: that it was not me, but another drunk guy started a brawl, hit his girlfriend, and started to throw furniture around. And he said about me: "This guy was in a fur coat, it was obvious that he just came in from outside. I have nothing against him. The shard that he threw just scratched my head a little bit, that was all." We met at a later time. "I was just standing there with my mouth open, when they announced your sentence. Six years for a silly scratch," - he said. At the trial, the man who was injured in the fight told the truth anyway: that it was not me, but another drunk guy started a brawl, hit his girlfriend, and started to throw furniture around. And he said about me: "This guy was in a fur coat, it was obvious that he just came in from outside. I have nothing against him. The shard that he threw just scratched my head a little bit, that was all." We met at a later time. "I was just standing there with my mouth open, when they announced your sentence. Six years for a silly scratch," - he said.

Even the convoy guards felt empathy, they whispered: "One guy here really did a lot of bad stuff, and they let him go. And you, kid, they really dumped on you, you should write an appeal."

At the correction zone, they first of all ask the new ones about why they were in - what article, paragraph, etc. The experienced prisoners listened to me, and reproached me: "Why did you try to cover up for a procurator's son?"

They gave me advice how and where to write a letter for appeal, requesting to have the case reviewed. But it was all useless. If the procurator's son had been brought in together with me for hooliganism, it could have made serious problems for his father's advancement in service and in transfer to Kyzyl from the district, so everything possible was done to keep me in jail alone and for a long time.

YOU WILL ROT IN JAIL - I PROMISE

- Where did you do your six-year sentence?

- In Ak-Dovurak, at the corrective-work colony with reinforced regime, or ITK-3. It is not there anymore. But in 1985, when I was sent there, it was a huge facility: the prisoners constructed large objects, built residential houses. So I also took part in the building of Ak-Dovurak.

There was everything you could imagine in the warehouses of the colony: cinder-blocks, lumber, everything you could need for construction. One day a truck came for a load from Sut-Khol hospital. My step-father turned out to be at the wheel. The guys decided to play a prank on him, and joyfully informed him: "You are Kongar-ool's father, right? He is doing time here, we'll call him right away, you'll be able to visit like family." He was so frightened that he did not even stop to load the truck, and left empty.

When they told me about this, I was very surprised that my step-father was so afraid of me. But that is how it worked out: I was terribly afraid in childhood that he would beat me up again, and now that I was a convict, I became frightening to him. But we did not meet. I only heard that he died in the middle '90's.

I did not have to stay the full six years at the colony. I was lucky: the October Revolution in 1987 helped - an amnesty was declared for the 70th anniversary, including those who had already done one third of their sentence and were not malicious disturbers of the regime at the corrective-work centers.

A commission met, the supervising procurator Trofimov asked me several questions, and announced that Ondar qualifies for the amnesty.

So instead of four more years, I had to do only another two years at the ITK "Kara-Dash" - that is what we convicts called it.

Only the procurator, my friend's father, did not like it. He visited me at the zone, and asked: "You still have two more years?" I answered: "Yes."

Then suddenly he attacked me: "Why do you keep sending letters to my son from here? Do you want him to bring messages to you, or what?" and I asked back: "But remember what agreement we had?" and he went wild: "What are you talking about? What agreement do you mean?" And then he went on; "Artyp kalgan churttalganny domzak duvu dyrbap tondurer sen - kai-daa barbas sen!" - "You'll rot in jail, you'll stay here for the rest of your life, I promise!"

I did not answer. He was a procurator, and I was only a convict without rights, what kind of a discussion can there be?

But one day my mother came to visit, and she started to reproach me: "What are you doing? Why did you order to have the procurator's son beaten up and all his teeth broken?? You are sitting here, writing to your friends to take vengeance for you outside, and it is torture for me!"

I did not understand anything, because it is not my way, this sneaky vengeance. Then it was explained that he and his friends got drunk on the beach - they were washing down a victory in a competition. They had some dispute and fought. And that is how he got his teeth broken. Then his parents decided that I have sent my friends, and began pressuring my mother: you will be responsible, and will have to pay for our son's new teeth. I did not understand anything, because it is not my way, this sneaky vengeance. Then it was explained that he and his friends got drunk on the beach - they were washing down a victory in a competition. They had some dispute and fought. And that is how he got his teeth broken. Then his parents decided that I have sent my friends, and began pressuring my mother: you will be responsible, and will have to pay for our son's new teeth.

THE BLACK STONE OF THE ZONE

- "Kara-Dash" means "Black stone". What gloomy poetry is in this unofficial name of the zone.

- It is a very accurate name, because the years spent in the zone hang like a heavy black stone on a man's fate. Many, even after being released, can never get rid of this black stone.

It is really very hard. For many it is impossible.

Among those who were there with me, were some excellent talented people - athletes, musicians. They did not end up in jail because of some serious crime, but mostly for hardly anything - some fight, where there was not even much blood spilled. Simply some small brawl for a girl or to show off, as it often happens when you are young.

But life in the zone is proving ground for durability. Neophytes get broken. They are factotums: they take orders from older experienced inmates who are doing a long sentence. They make chifir - very strong tea - for them, and serve in everything.

In a way, there is nothing one can say against them. They are elders - authorities, and if you do everything right, they always help you, but there are real bandits behind them. They have ways of dealing with those who resist - grab then by hands and feet, and smack them on the cement floor…

Try to live every day with such stress: always running errands, constant humiliation, breaking yourself for years, trampling your pride. It is the most difficult part of being in the zone.

That is why many guys who had short terms in the colony, came out psychically disturbed, angry. They could not show themselves in the zone, so they showed off outside, at home: "I am so tough!" And they took out all their frustrations and humiliation on their families, turning the lives of their relatives into hell. And soon enough they were back in jail.

It is not possible to put neophytes together with experienced convicts - authorities, it is better to punish small crimes by suspended sentences.

- You, as a neophyte, did you also have to suffer all the humiliation from the experienced convicts?

- No - not me. Those who had some talent won some authority right away, not by the length of your term, but through your abilities. Those were not bullied and intimidated.

And in the zone, athletes were very respected - wrestlers, volleyball players, who were good in competitions at the colony.. Also artists who could write a letter in a beautiful script, with a beautiful drawing, to the outside, or make an astonishing postcard for a beloved woman.

They valued craftsmen who could carve wood and make a keepsake box, or a frame for a photo with lovely patterns. And they sewed covers for photo albums - real beauty. There were such artists!

Artists were also very respected. We founded an ensemble and gave concerts at the colony club on holidays, the administration encouraged amateurs, it was believed that music and songs help to re-educate the convicts.

And the "authorities" also asked us to give unofficial concerts when someone of them was being released, or, on the contrary, if somebody they knew was coming in. These were festive occasions - even chocolate candies and cocoa, which were prohibited in the colony, could be seen there. And they treated the artists to them; on ordinary days, a spoonful of sugar or a piece of a sugar cube was a rare treat.

There were also kind of parties after supper, before lights-out, when the convicts were already in their group barracks. They would set up a table in the aisle between the cots. The cots were in three levels. The most inconvenient and uncomfortable cots were on the third level and near the door, the new ones and those who were being bullied slept there. The most honorable spots were in the corner, and definitely on the lowest level, that is where the authorities were located. These parties could sometimes go on all night. In that case, one of those underlings would be assigned as the look-out, in case some supervisor showed up.

Khoomei was always welcomed with enthusiasm at the concerts, and they always exhorted me: when you get out, you will definitely become a great artist and make our Tuvan khoomei famous throughout the country.

A WHOLE SET OF THREE PRESIDENTS

- And it really turned out just like they told you at the zone: you made khoomei famous. And you performed khoomei for all three presidents of the country - in turns.

- Really, it was the full set of three presidents - Yeltsin, Putin, and Medvedev. I met all three of them and sang for them.

For the first president of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, I sang on June 16, 1994 at Chagatai lake. They welcomed him in Tuva that time with great festivities, built yurts by the lake - really beautiful. And there, in fresh air, I sang khoomei.

By that time Boris Nikolayevich was already dressed in the Tuvan coat that they gave him, had already tried araka, and evaluated it, but he still could not believe that this Tuvan moonshine was distilled from milk. So they specially brought him to see a shuuruun , (traditional still-HJ) which stood on a fire by the yurt. His bodyguard was holding him back: don't go near it, everything is boiling! But he: don't hold me! He tried it and was astonished: really, it is milk, just imagine if we collect all the milk in Russia, how much araka there would be!

Then they seated the president under a tent, and the concert began. I sang. Suddenly Boris Nikolayevich jumps off the chair and runs up to me. He commands: "OK, do it again!" he through that I was holding something in my mouth, and that is what made those weird sounds. He stood over me looking into my mouth, to see if I was hiding something.

I was even anxious for a moment: I am not a big guy, and there was this big president hanging over me, peering into my mouth. What to do? I had to sing, what else could I do, I am supposed to be an artist.

I was looking at him from below, and singing he listened with such interest, then he asked again: "Once more!" I sang some more. He applauded. Then he took my hand and raised it up: "What a talent! Does he have some Russian title?" They answered him: "No."

At that time Evgeniy Sidorov was the Russian minister of culture. Yeltsin pestered him: "Sidorov, how come this is the first time that I hear this unique talent?" "Boris Nikolayevich, I have not heard this before either." "What kind of a minister of culture are you? Give him some title!"

After that they gave me a title right away, already in October - Merited artist of Russian Federation. And not just to me, but to many other Tuvan artists as well. They sent a whole file of documents from Moscow, and they all passed: artists as well as culture workers-officials got Merited titles.

And for Vladimir Putin I also sang outdoors in Tuva: on 14 August 2007 on the bank of river Khemchik, at Shanchy-Aksy. Sergei Shoigu often goes to this place, he loves to vacation there. This time he came along with Putin. It was night, bright campfire burning, and us the throat-singers gave a concert. We sang all night.

Putin shook our hands, and told us, that there is a painting by some famous painter, I forget the name, which has such a bright moon on it that people do not believe that it is only painted, and all the time try to look behind the picture, to see if there is a lightbulb there. He admitted that he also wanted to take a look inside, to see how we produce such amazing sounds. It was a very warm, friendly meeting, completely informal.

I met Dmitri Medvedev under official circumstances in Moscow: in 2011, on 24 March.. I remember the date very well, because my son was born the next day in Kyzyl. I thought then: if the dates were exactly the same, I would have named my son in honor of the president: Adyg-ool - Bear. (Medved = Bear. HJ)

There were many people at the meeting with the president at the Multimedia Art Museum: writers, composers, directors, painters, singers. The time was limited for each performer, but I sang 35 seconds of khoomei.

And I managed to tell him about our problem: officially the khoomeizhi profession does not exist.

Medvedev promised to concretely solve the task. And it was solved: a new profession appeared in Russia: artist of throat-singing - khoomeizhi. It was added by the minister of health and social development of Russia into the United Registry of Qualifications.

So now we are working on solving the problem of pension benefits, so that Tuvan professional throat-singers could go to their deserved retirement after fifteen years of stage performances, just like ballet artists or opera singers. After all, khoomeizhi is not an easy profession, it has an effect on health, it has even been proved by scientific research.

PUNITIVE ISOLATION - JAIL WITHIN JAIL

- And how is your health, as you are a professional khoomeizhi?

- I have no complaints, but I do have high blood pressure: 190/120 normally, and one time they even measured 240/140! But so what - I keep singing, even though the tension is great.

But the consequences of the zone still show up in terms of health. Life in the zone is a constant trial of strength. The order there is brutal.

In October 1986, they took me to the duty room to the senior lieutenant because I broke the rules - I walked between the barracks, and that was prohibited. That day the service aide of the colony chief was on duty. I don't even want to mention his name. In October 1986, they took me to the duty room to the senior lieutenant because I broke the rules - I walked between the barracks, and that was prohibited. That day the service aide of the colony chief was on duty. I don't even want to mention his name.

He threatened me: "I'll throw you for fifteen days into isolation." Ok, I think, I'll be locked up. November passed, December began - all was quiet. I was relieved: the chief had forgotten, or maybe he was only trying to frighten me.

But it was not like that. On 29 December we were rehearsing at the club, getting ready for the new year concert, and the senior lieutenant showed up with two soldiers. He stood there for a while, looked at me attentively, and left. But after supper, they called me: "Convict Ondar, report to the duty office!"

He sits there, the senior lieutenant, he is again on duty at the colony, and tells me cheerfully: "I have a surprise for you!" The explanation that I wrote up back in October is on the desk.

"It was like that", - I said. "Read it carefully, it continues," - he tells me. And I read: "Fifteen days of arrest for breaking the prison rules." And the date is 29 December 1986.

I grabbed at a straw: But what about New Year, chief? I am supposed to play in the concert." "They'll manage the concert without you, and you will meet the New Year in isolation."

- Nasty rumors went around about the isolation: jail within jail, where one gets tortured by cold and hunger. What was it like at ITK "Kara-Dash"?

- That is exactly what it was: a jail within jail. In the corner of the zone, behind a cement wall, there was a cement building. A narrow corridor inside, with tiny cells along it. A dull lightbulb in the corridor, no light in the cells.

There were different cells. The PKT kind were of room type, where people were kept for three to six months. There were even beds there: they would be let down at night and raised up in the morning. During the day the prisoners sat on the cement base of the beds.

But the punitive cells, where one was put for fifteen days, had no beds or anything. Simply a tiny empty cell behind a double wall: first bars, then a door. Walls, ceiling, floor - all cement.

There were three of us in that room. We slept on the floor, closely curled up together. As soon as somebody's hip began to freeze to the floor, he would say: "Shu-de!" and we all together turned over to the other side. The one in the middle was the best off - he was being warmed up from both sides. We took turns, so that it would be fair.

So the rumors about the cold are true, and about the hunger as well. The food was of summer kind, and non-summer kind.

- Summer and non-summer diet in the isolation - is it a kind of humor?

- Yes, it is the humor of punitive isolation. You could do one of two things: cry or laugh. And because men are not supposed to cry, we had to laugh.

Non-summer and summer days alternated. Non-summer weather meant that for dinner, they brought only water in aluminum bowls. And in summer weather you get water with shreds of cabbage or oats floating around in it. That cold swill was not edible. But we ate it anyway - because of hunger.

It was good that they gave us bread three times each day: that is the assigned ration for a convict. The ration was like this: the loaves were divided into five parts. You got one fifth of a loaf as your ration for breakfast, dinner and supper. Altogether you got slightly more than half a loaf every day. And that was all the food in the punitive isolation. So you sit there in the cell without getting out for your term, without any walks.

But there were entertainments.

THIRTY BUCKETS OF WATER AND ILLEGAL INJECTIONS

- And how did you entertain yourselves in the cell?

- We did not entertain ourselves, it was the guards who entertained themselves over us. And I experienced their jokes in full right after the first night in the cell.

Early in the morning, at five, the door noisily opened, and we jumped up, standing at attention. The officer, whom the convicts nicknamed Kara Kadai - Black Old Woman, asked: "Prisoner Ondar, what date is it today?" I answered: "The thirtieth." And I heard the answer: "Down!"

At that moment I realized immediately that I made a mistake. Other guys warned me, that whatever number at the isolation you'll say, that will be the number of buckets of water that you will have to pour into the corridor and wipe dry. I should have to think fast and turn it into a joke, answer for example - it is the first day, chief. It might have worked.

But once I said thirty, I had to pour out thirty buckets of water. There was a faucet with cold water in the corridor, hot was not allowed. I took off my felt boots, socks, rolled up my pants, and stated to pour water on the cement floor, then wipe it dry. I had only one thought in my head: "Faster! Faster! Faster!" My feet turned to ice and lost all feeling, but steam was coming out of me, sweat pouring in streams. Somehow I finished. But once I said thirty, I had to pour out thirty buckets of water. There was a faucet with cold water in the corridor, hot was not allowed. I took off my felt boots, socks, rolled up my pants, and stated to pour water on the cement floor, then wipe it dry. I had only one thought in my head: "Faster! Faster! Faster!" My feet turned to ice and lost all feeling, but steam was coming out of me, sweat pouring in streams. Somehow I finished.

Then back in the cell, the guys massaged my feet, trying to warm them up by breathing on them, to bring the feeling back. Guys from the other cells shouted advice: "Ondar, quickly lay down on your abdomen, and put your feet up on the radiator." Somehow I came back to myself.

- So this was no re-education but outright mockery, which was not foreseen by any regime of custody. Wasn't it possible to refuse, to stand up for your rights?

- What rights, what are you talking about? Yes, it was outrageous, mockery, but it was very smart, it was impossible to prove. If I had refused, the officer would have written a report right away: the prisoner refused to work - refused to wash the floor. And the management would immediately come to the conclusion: so he breaks the rules even in punitive isolation?! Another fifteen days for him!

Then I figured it out, I thought: I am sure that the procurator could not stop thinking about me, he really wanted me out of this world, and he arranged for the punitive isolation for me, and the thirty buckets, so that I could never tell anybody anything.

To run around barefoot in such cold, on a freezing floor in freezing water - that was a sure way to get pneumonia or even tuberculosis. Very many young kids came out from the camps sick, and died young.

I also got terrible pneumonia from the punitive isolation - it is awful to remember. I went to the infirmary, and the doctor laughed, broke up a pill in two halves, and said: "This one is for the headache, and this one for the fever."

So I pretty much collapsed. I remember hearing my countrymen from Dzun-Khemchik district, kids from Chyrgaky and Chyraa-Bazhy saying about me: "He is really bad, if you don't help, we'll lose him."

And the others helped, somehow they got a hold of some ampoules of penicillin. Despite strict control and security, many things that weren't supposed to did get into the zone. Experienced people had their ways and channels.

Once even a photo-camera "Smena" got in, and we took photos right in the zone. Then the camera disappeared just as quickly, but I still have the photos. Only many of the people on the photos - my age mates - are not alive anymore.

Vova Bady saved me that time with injections of illegal penicillin; he was a prisoner with a good job - at the school; where those who did not have intermediate education could study. So Vova boiled the syringes on the burner at the school laboratory - back then disposable syringes were not even heard of.

At noon, when the teams went to lunch in a torrent of people, I quickly, unnoticed, jumped over the gate to the school. Bady was already expecting me there, gave me a fast injection, and I snuck up into the torrent of people again, so that nobody would notice my absence and accuse me of breaking the rules again.

The injections helped - I got well, but I still suffer from the consequences of the pneumonia: if I just once walk on the floor barefoot, I get sick right away.

IT ALL STARTED WITH A BUTTON

- Kongar-ool Borisovich, and what about that terrible prisoner revolt which was suppressed at ITK-3 in the middle Eighties?

The very short history of Tuvan camps, which is now available on the web-site of Administration of Federal Correction Service for Republic Tyva, of course, does not mention it at all, but because you were an inmate there at that time, perhaps you could help clear up that blank area of history by giving us your version of those events.

- Yes, I was an eyewitness. And I remember the exact date - 13 may 1986, and everybody who was an inmate there at that time remembers it as well, because it was terrible.

Only there never was any armed revolt of the prisoners. It all started with a button. The administration demanded that everybody should button up their jackets completely, including the uppermost button. Some buttoned up, but others did not: they said that this was a facility with reinforced regime, but not special regime, and we were not in the army. So they began to squeeze them, but the guys did not button up anyway, and continued to murmur.

And then the outrage began: A report went out that the prisoners were revolting. The army was called in, soldiers in helmets, with nightsticks, and shepherd dogs barking.

There were about fifteen hundred inmates there at that time. They herded everybody behind a fence, like a herd of sheep, and began calling up names of those whom they considered the initiators of the revolt, the authorities.

They were loading them up into a covered truck, like cows and horses to a slaughterhouse. To get to the truck, they had to run through a very narrow corridor, with soldiers and their shepherd dogs alongside. The soldiers would speed up those who were walking in that corridor with their nightsticks, beating them, and sick the dogs at them. So the inmates did not walk but run to get faster to the truck.

Everybody fell silent, terrified that his name would be called. I was frightened too, after all, as an artist I had some authority too. I had only one thought in my head: if they call me, the most important thing is not to trip and fall, the they would kill me with those nightsticks, or those running behind would trample me to death.

The truck was already full, stuffed to bursting, yet they kept calling more names. The prisoners were screaming, clambering over each other, dogs were attacking them. Just like a meat-grinder! Streams of blood!

Things can't be done this way. Even though they are only prison inmates, criminals, they are living people after all.

That truck would normally take a hundred people, but they stuffed in twice as many. They transported two hundred people out of the zone, and, as they said later, those were separated and distributed through other colonies.

So the zone was a place where one had to survive all the time. Today inmates have so many rights that we never dreamed about in Soviet times! And today's colonies in comparison with the previous ones are just pioneer camps.

ITK "Kara-Dash" is long gone. Once when we played in Ak-Dovurak, I took the kids - young artists - to the ruins of the zone. The cement isolation building was still there, without the roof. I pointed out the cell where I was locked up, the kids were surprised, but, I think, did not really understand what it was all about, but I had chills running down my spine. It is difficult to understand if you have not been through it yourself. And it is much better to never have to live through something like that at all.

TO REMAIN HUMAN

- What is the main lesson you learned at the zone?

- To remain human.

- And were you successful? When you became a famous and respected person, did you ever seek vengeance on those who harmed you?

- After all, truth always wins over a mountain of lies. Why try for revenge and wish people harm?

When I was elected a delegate of the Legislative House of the Supreme Khural of Republic Tyva in 1998 for Dzun-Khemchik district, the career of the procurator, my friend's father, was at one point in my hands. And I helped him.

Delegates at the session were supposed to vote for or against his candidacy for a high post. He did not lift his eyes to look at me. I was looking at him, thinking: "What interesting tangles of fate. He promised to see me rot in jail, and now here he is, dependent on me."

And I proposed to do open voting. Secret voting has always been dangerous, even candidacies of ministers never pass on the first try. But with open voting, few people want to make enemies by voting against. They took my proposal, voted openly, and he got his high post that he wanted so much.

And the senior lieutenant, who arranged the punitive isolation with an ice bath for me, was also appreciated at work, true, without my help: he is now a colonel.

One day, as I was returning from a tour abroad, I ran into him at the airport. I shouted cheerfully at him: "Ekii, darga!" I greeted him like we did at the colony, calling him darga - chief. But he looked at me strangely and tuned his eyes away.

THE BIRTH OF THE FIRST THROAT-SINGING GROUP - "TYVA" ENSEMBLE

- Kongar-ool Borisovich, how did khoomei enter your life?

- Very simply and naturally - from early childhood. Relatives used to place their yurts close together at the summer herding encampment. They took care of their cattle together, helped one another, and sometimes, on evenings, they gathered in our yurt.

It was always preceded by preparations: araka was made - milk vodka. Those were not preparations for a drunken party, but for a holiday, which I awaited with impatience: there would be a concert, interesting discussions, and khoomei until dawn. My feet hardly touched the ground when I ran to get water and wood for the distillation apparatus - shuuruun.

As the araka was

|